Patch #31: The big small stores of the future

What if the future of retail is no longer Amazon?

1. Fast Times at Ridgemont Mall

A few weeks ago, I re-watched the 1983 movie Fast Times at Ridgemont High. The film, set in a fictional high school, reflected the real-life experiences of Cameron Crowe in Southern California in the early 1980s. We all know what’s great about the movie: Brad’s pirate uniform, every scene with Spicoli, the indignities heaped upon Mr. Hand, and so on, but watching it after not seeing it for fifteen years or so, what really struck me was the sheer glory of the mall scenes. Here, preserved in Panavision amber at the apex of a collective fascination with the mall, is a perfect representation of the mall as not only a place to shop, but a place to socialize, try on an identity, and refine one. I was hit by a wave of nostalgia, potentially misplaced, about how easy it used to be to feel connected to a single place and time: everyone traveling in similar patterns, dressed in variations on a theme, out in the world, interacting, waiting for things to happen.

The mall of the early eighties has everything you need, including tactical niceties like ample parking and spiritual ones like the ability to mainline abundance should you feel its lacking. At Ridgemont Mall, everyone is beautiful and the night is filled with possibility. The movies are probably terrible, but the usher wears a tuxedo. The food looks pretty bad, but that’s okay because no one is taking pictures of it with their phones. No one has phones. The interactions happen in a parallel universe where nothing is recorded and no one is distracted. I used to go to the Perimeter Mall in suburban Atlanta in the early eighties and my sister would tell me to walk behind her and walk cool but not too cool and I learned, even as a first-grader, that commerce was hardly the point.

Let us compare to the way we likely shop now: with a phone, while doing something else. During the pandemic, out of an overabundance of caution, norms shifted so that, in rapidly multiplying contexts, you no longer had to interact with other humans in many transactional settings. Without any action on my part, my Doordash account preferences shifted to “Leave food at door,” and though I’m very aware I can change those preferences and greet the individual who was kind enough to bring me my dinner, I do not. The spectral allure of convenience is too strong. It whispers to you like a devil on your shoulder, pushing aside more abstract moral concerns about the future of a society where no one talks to each other and privacy only exists in isolation.

Imagine, for a moment, how comparatively inconvenient it would be to venture to the food court at Ridgemont Mall to pick up a slice at Perry’s Pizza. One would have to get in a car, and park, and, after a wait in line for a table, pay Stacy Hamilton for the trouble, and probably wait for her to make change. But these layers of friction that exist in the Perry’s Pizza example do have some value, impractical though they may seem from the outset. Let’s start with the most obvious one first: you might talk to another human being in real life, see someone you know, or even have a chance encounter with someone you don’t know. You would also get in your car and, perhaps, admire the setting sun over the miles of sprawl and freeways in the San Fernando Valley, a scene that, ok, is not exactly the Aspens turning on 285, but is not without its virtues or textures and their associations with a certain time and place. And perhaps you would have listened to the eternally great, slow-burn Cars track “Moving in Stereo” on your way, which would have burnished the scene out your windshield with technicolor dimensionality and filled you with a probably misplaced belief, mentioned in another Cars song, that “it’s all gonna happen to you.” You might have turned it up until the plastic speakers in your car tizzed and thought I’m not driving a sub-par shitbox, but a goddamn spaceship. Why not? The future, after all, was filled with possibility. Once you parked this spaceship, you had to walk into the mall, pick up the pizza, and walk back, meaning you would actually move instead of sitting, shrimp-like, with your head craned toward your screen of choice. The occasion might have even been social. I’m going to Perry’s? Want to come?

The night was filled with possibility, but it wasn’t especially convenient. Certainly not frictionless. In years of designing for hire, I learned convenience was one of two things that, when push came to shove, customers weighed carefully (the other being cost). The customers would say they cared about other things: higher-order aspirations of the more admirable sort, but they would not place those values over the twin pillars of convenience and cost unless there was a really good reason to do so. In many cases, you’d have to compete against cheap and convenient, and if you were only going to be one of those, you had to pull ahead of the pack to abandon the other. I always found the logic damning but irritatingly correct in practice. Low-cost, high convenience products would usually win unless hard-won brand attributes such as exclusivity or quality or other associative elements entered into the purchase equation.

Pre-mobile, building such associations was both difficult and expensive. When I was younger, I worked with people who still remembered the advertising budget bonanzas of the nineties and early oughts, when companies large and small did everything in their power to ensure they built, maintained, and multiplied a carefully crafted brand persona that would drive people to forsake the allure of cheap convenience and reach for shiny objects on the shelf. But before we talk about what happened and what might happen next, let’s consider the story of one of the retailers that anchored many a mall like Ridgemont before these temples of commerce ended up as fodder for the YouTube channel Retail Archeology.

2. The Big Store

It’s worth noting that when Fast Times was filmed, the dominant retailer in the U.S. was Sears. While the leadership team of CEO Edward R. Telling sliced miniature carrots sliding around on bone china in the lavish executive dining room in the tallest building in the world, they contemplated how they might turn its position as one of the world’s dominant retailers into something much, much bigger. Aside from their expansive view of Chicago, the company had other reasons to be confident. Sears, after all, had been responsible for a range of disruptions: first the catalogue that allowed people to order goods from the comfort of their home, then the massive retail footprint that would define the big box era: a huge store, plentiful parking, and prices and goods attractive enough to draw visitors.

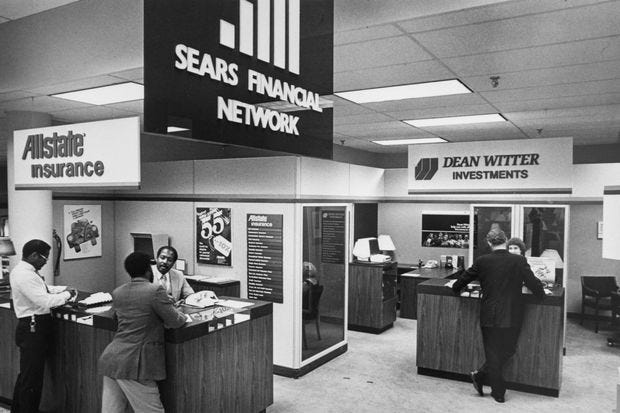

Telling and his team were focused on a strategy that was much bigger than just retail: diversifying into insurance, real estate, and investing in order to more broadly meet the needs of its then loyal and massive user base. All of this is entertainingly told in Donald Katz’s highly recommended book The Big Store.

Sears could spin a grand, gilded net for the people that included housing, mortgages, all manner of insurance, variations on banking sources, investment services, and, of course, consumer goods. People could get a house from Sears again. When the system was up and running, they could even get the money to buy the house; get the stuff that goes in the house; and the services that ensure the sustenance of the house if something unforeseen happens. People would be able to save their money at Sears and spend it there too, and perhaps some day the whole thing could be intricately connected by machines. People's televisions and telephones would connect them to the system. Sears, Roebuck could become the chassis for the whole of a citizen's material life.1

Some critics made light of Sears’ ambition to sell “socks next to stocks,” but there was a rationale. As Katz also points out, Sears had a massive data advantage. The combined master file of Sears, Allstate, Dean Witter, and Coldwell Banker customers by itself contained the home addresses of more than sixty million of the eighty-four million families in the United States. If Sears could create a data-enabled relationship with each customer by utilizing the combined information at the newly conglomorated entity’s disposal, it could leverage these synergies as Katz describes in a way that feels very recognizable to us today as customers of Amazon: relationships at scale, with convenience and value right at the top of the menu.

With hindsight, the strategy looks flawed at best and lethal at worst: an expensive gambit that knocked the once-proud corporation from its pedestal, ultimately making it vulnerable to its ignoble decline at the hands of Eddie Lampert and his posse of cost-cutting, blood-sucking MBAs in Greenwich. The truth is more nuanced. Sears saw justified potential in their strategy, but feared violating the hard-earned trust it had won with its customer base. Telling, after all, was a merchant at heart, a man who grew up in stores and liked to lay hands on the goods and arrange them just so, even as he climbed to the top of the sprawling organization. He worried that too much cross-selling and optimization of these relationships would diminish the all-important trust quotient and that the result would be ruinous.

Here is Katz writing once again in The Big Store:

The corporation's relationship to a hypothetical customer who had just purchased a child's car seat from the catalog was deemed too valuable to risk losing his or her future business because of a call from an Allstate person trying to sell more life insurance to new parents, or from a Dean Witter broker offering zero-coupon bonds for college tuition.2

In other words, bigger isn’t always better: synergies on paper, even those that deliver better convenience and value, are worthless if they damage customer relationships. This is because the collateral damage to a brand might be so great that it leaves that brand defenseless to the dreaded commodification/ race to the bottom of competition on price and convenience alone. Ultimately, Sears unraveled its conglomerate by selling off the component pieces. As Peter Drucker put it in a 1994 HBR article, “The move was a total disaster. The U.S. public clearly did not consider its financial needs to be consumer products.”3 Sears tried to return to its retail roots, but the relationship with its customers had weakened: squeezed by higher-end retail on one side, such as could be found in upscale department stores, and discount retailers on the other, especially Walmart. The story is told now as a cautionary tale about hubris, forgetting what you’re good at, and failing to evolve with the times. If we think a bit about the future of retail, however, I think we can find lessons in the remains that are a little bit more nuanced.

3. From big stores to big small stores

I recently interviewed a bunch of folks with deep technical chops in AI, including several who had successfully started and sold AI companies. Thinking back on these interviews, one of the things that strikes me is several of the subjects shared a similar idea about the future of retail: a vision of a small, excellent store that uses AI efficiencies to scale, but doesn’t sacrifice intimate customer relationships to do so. One interviewee told me to imagine a hardware store where the owner knows your name, the kinds of projects you work on, and the best tools and fixes for your specific needs and goals. Here in Colorado, that might look something like McGuckin Hardware in Boulder, a store those in the know, like my friend Zack, speak of with a near-religious reverence one doesn’t often encounter in reference to a place where you buy mulch, safety glasses, and drywall anchors. If you dig deeper, loyalists will tell you it’s all about the “green vests” who define the in-store experience: seasoned tradesmen who love what they do, enjoy connecting with customers, and are likely to have been there for many years.

The problem is there is only one store, and scaling McGuckin would introduce the need for efficiencies: new departments, new protocols, more employees, more lawyers, more compliance training, more complex systems to run it all, and so on. Justifiably, those in charge of the store might worry that, in addition to bringing in folks with vampiric, Lampertesque sensibilities, expansion might vitiate the essence of a store that was, after all, founded in 1955 by a man named Llewellyn Commodore “Bill” McGuckin.

But what if you could? What if scale didn’t necessitate cavernous, impersonal stores, a la Home Depot, that rely on an app to help overwhelmed customers find what they actually came into the store to buy? What if you could push resources into doing exactly what it is that makes one store great—building customer relationships one conversation at a time, over time—and copying it elsewhere?

Until recently, the answer might have been something to the effect of that would be great genius, but you can’t have your cake and eat it too. With scale comes costs. Stores that are in the business of scale might do best to lean harder into sameness and consistency, ensuring that a store in Burbank and one in Boulder feel more or less the same. People go to McGuckin for personalized relationships; they go to orange hell for convenience and value. Or maybe they just order it from Amazon or Grainger and skip the store altogether.

But using these options not only means foregoing connection to the place where one lives (or visits), it means foregoing relationships that will likely deliver increasingly more value as they build. In the big small store concept mentioned by those I interviewed, businesses are able to prioritize the value of these relationships even as they scale because of newfound abilities to automate time-consuming processes like inventory management and HR needs (among others).

The resulting world might be one where local businesses, even chains and franchises, are less defined than what we’re used to. Back in the day at IDEO, I did a lot of brand strategy projects, and this idea goes against everything I preached about building a brand presence. Namely, that brands should pursue a rigorous, relentless consistency and avoid the temptation to be all things to all people (and thereby risk becoming no thing to no one). Looking back, it occurs to me that this idea was necessitated as much by the practical realities of exercising control over distributed experiences as it was about any inviolable laws of branding. Indeed my clients, for the most part, were massive corporations or those who aspired to become that way.

This might be changing. One fascinating experiment playing out before our eyes is the case of Barnes & Noble, the maybe-moribund bookstore chain disrupted by Amazon, who is trying to fight back against the everything store by making itself look more like the local bookstores it disrupted in the first place. This is all well-documented in the New York Times article here. Aside from winning favor by snarking that a previous strategy to turn the store around made the stores resemble “the discount aisle at Spencer’s,” the article is full of casually heretical ideas about how to save retail, most of them articulated in plainspoken comments by B&N CEO James Daunt. For example, asked what his strategy for the turnaround is, Daunt says, “You turn what had been a very uniform but dying business into something that’s much more unpredictable and dynamic, and it begins to work.”4

It’s worth pointing out that, though there are signs of promise, there is no telling if Daunt’s effort will actually help Barnes & Noble thrive in the marketplace over time. I also see no risk of Amazon disappearing any time soon. Judicious bettors would be well-served to place their chips on a world where physical stores and hyper-convenient online juggernauts proceed in parallel. When I speculate that the future of retail may not be Amazon, what I mean is that the excitement and best part of our aspirational selves will not scale commensurately with more convenience and value and efficiency. The enshitification of our Amazon feeds by semi-counterfeit goods that are too expensive for what they actually are—knock-offs of established brands who have paid for play to be moved up in priority—cannot go on indefinitely.5 Come to think of it, our Amazon feed already feels like the discount aisle of Spencer’s, or Lampert’s desecrated millennial version of a once-proud Sears. We might buy batteries there, but will we buy things we actually care about?

The Goliath will endure, but new Davids might rise up in the form of unpredictable and dynamic retail experiences; small stores with big, vastly more efficient backend systems; stores that are suddenly better positioned to prioritize relationships and managers and employees who know their customers. Some of them will probably be owned by Amazon. Either way, there will be a whole lot more McGuckins, and that is something I’m personally looking forward to, even if I have to go to the mall to find it.

This week’s recommendations:

Reading: Hard Rain Falling, by Don Carpenter

Listening: Lahai, by Sampha

Music credits for article audio:

Opening Theme: “Cepheid Disk” by Airglow via Wikimedia Commons

Closing Theme: “Comfort in Uncertainty” by bbatv via Wikimedia Commons

Katz, Donald. The Big Store: Inside the Crisis and Revolution at Sears. Penguin Books, 1987.

Katz, Donald. The Big Store: Inside the Crisis and Revolution at Sears. Penguin Books, 1987.

Drucker, Peter F. "The Theory of Business." Harvard Business Review, vol. 72, no. 5, Sept.-Oct. 1994, pp. 95-104.

O'Connor, Maureen. "Barnes & Noble Sets Itself Free." The New York Times, 17 Oct. 2023

Doctorow, Cory. "Social Quitting." Medium, 15 Nov. 2022