Photo via Wikimedia Commons

X: Tell me again about how the bicameral mind began to break down.

Y: Jaynes suggests that the bicameral mind began to break down around the time of the Bronze Age collapse (approximately 1200 BC). Factors such as increased societal complexity, the development of writing, and the emergence of new religious and philosophical ideas contributed to this shift.

The breakdown of the bicameral mind led to the development of human consciousness. Jaynes argues that this transition was marked by the growth of individual self-awareness, introspection, and the ability to construct mental narratives. This new form of consciousness allowed for greater autonomy, decision-making, and problem-solving.1

X: Let’s start somewhere else. Let’s start with a memory. Take down spoken text word for word. Smooth later.

It’s 2014. I’m in a consumer research facility on a quiet street in the outskirts of Mexico City, there as part of a well-funded contingent trying to design a new breakfast snack. The contingent includes two consultants from the company that invented the Frappuccino, two industrial bakers…a few designers and engineers and so forth. Maybe an exec with Tory Burch logo sandals and a North Face fleece who keeps looking at Instagram on her phone.

Despite our best efforts, the final design won’t be particularly disruptive in the saturated breakfast snack marketplace. It will start out healthy(ish), but waves of testers — in Mexico City, Atlanta, and London — will say the snacks aren’t sweet enough. The onlookers from the large consumer packaged goods company will nod knowingly and scribble notes in their notebooks. The product needs to compete with Mondelez’s popular Belvita breakfast biscuits, which are basically Oreos with protein. In the CPG world, everything eventually becomes a cookie or a potato chip. Granola bars, for example, are basically just oblong cookies.

X: Scratch that. Start again…this time let’s imagine a setting in the future, one that maybe speaks to the evolution of consciousness.

It’s 2037. We’re designing a new kind of wearable that will optimize the healthiest possible lifestyle choices for users. Maybe we’re designing this product in order to reverse the damage we did with our sugary breakfast snacks in 2014? The important thing is that the technology has promise, and we’re well-funded by a consortium of private investors and a Japanese pharmaceutical company. My NDA forbids me from revealing more, but I can tell you that we are doing this research in-person because one of the funders believes there’s no substitute for face-to-face interaction, especially now that it has become more scarce.

The expense of this excursion — we are a team of 8 now — is justified because of the product’s revolutionary potential. We’ve got a neuroscientist, two engineers, a psychologist, an interaction designer of considerable renown, a graphic designer, a botanical illustrator from Montreal who refuses to use technology of any sort, and myself: a lowly design researcher who is ostensibly running the process.

X: You are a set designer. Help me design the setting. Help me ride through the streets, step out of the hired car, walk into the building, and inhabit its strange and silent rooms.

I already told you that we’re on a quiet street in Mexico City and that we’re in an unexceptional suburb filled with mid-rise office buildings and residences. I no longer remember the name…choose any one that suffices. What I haven’t told you is that the office building is coated in a cream-colored stucco, and that it is clad in dark black windows that reflect back the foliage lining the street: Ash. Eucalyptus. Let’s say a Jacaranda in the courtyard. It must be late summer, then. Yes, let’s make it late summer. The leaves are thick and green. When we pull up in the autonomous black shuttle with our bodyguard, I’m struck by the way the tinted windows of the shuttle match the windows of the building.

X: One association: that hotel in downtown Los Angeles with the shiny windows. The famous one designed in 1976.

Y: The Westin Bonaventure?

X: Was that the one featured in the Buck Rogers show in the early eighties?

Y: Yes, this one.

Via Wikimedia Commons

X: That’s it. Windows like those. Oh damn look at that quote by Edward Soja.2 Please save that for future reference. Let’s keep going on the setting.

The room is acoustically treated and swathed in soft, textured variations of grey. The overall feel would be soporific, but the air-conditioning is cranking, and everyone is awake. The optimized acoustics of the room are such that you can whisper, and everyone still hears you.

Even if you’ve never had the pleasure of witnessing a focus group, you probably understand something of what the famous two-way mirror looks and functions like in these rooms. Unlike a regular mirror, the two-way mirror is painted on one side — the side where the subjects and their interviewer sit — with a reflective surface. This enables the viewers, who sit in a darkened room that feels a bit like the control booth of a recording studio, to look through the mirror from the other side and observe what’s happening in the room.

X: Why is it called a two-way mirror instead of a one-way mirror?

Y: It’s called both.

X: Weird. Anyway, keep going.

The research participants understand the layout. When they walk into these rooms, they often look toward the mirror and nod, acknowledging they know they’re are being watched. Whoever is hosting the session — in Mexico City, it’s often either me or Anna, the psychologist — explains the mirror and the presence of the observers behind it as a matter of professional courtesy. Most of the people who come to focus group facilities such as this one are regulars; they rarely have any questions about the arrangement. It’s unusual, but not without its pleasures: how often do we talk about our preferences and opinions and have not one, but a number of people hanging on our every word (even if they’re out of sight)?

I like leading these sessions and guiding our participants through the use of the prototype, but I also enjoy watching from behind the glass. Even though everyone knows the observers are there, it’s easy to forget their presence. It’s a rare thing, I’ve found, to watch people with absolute attention without feeling self-conscious about doing so. The more deeply you consider another human, the more complex they become.

The observation room is dark, whereas the room where the subjects are is lit with unattractive fluorescent lights. The observation room also has comfortable chairs, a space for one’s machine, drinks, snacks and, if the facility is a nice one like the one where we are in Mexico City, a quality AV system that pipes in the conversation from the next room. In such rooms, when I get the chance to observe, I find that I often feel a sense of incredible calm, that I’m loathe to get up from my seat and venture back into the interview room where I must conduct the sessions under the watchful eyes of the other observers.

X: Okay that’s enough of the setting. Now let’s make something actually happen.

I’m sitting in the observation room. Anna, the psychologist, is running the session. I think, once again, about how Anna is a better interviewer than I am. She’s breezy on the surface, but not in the performative and ingratiating way of some interviewers.

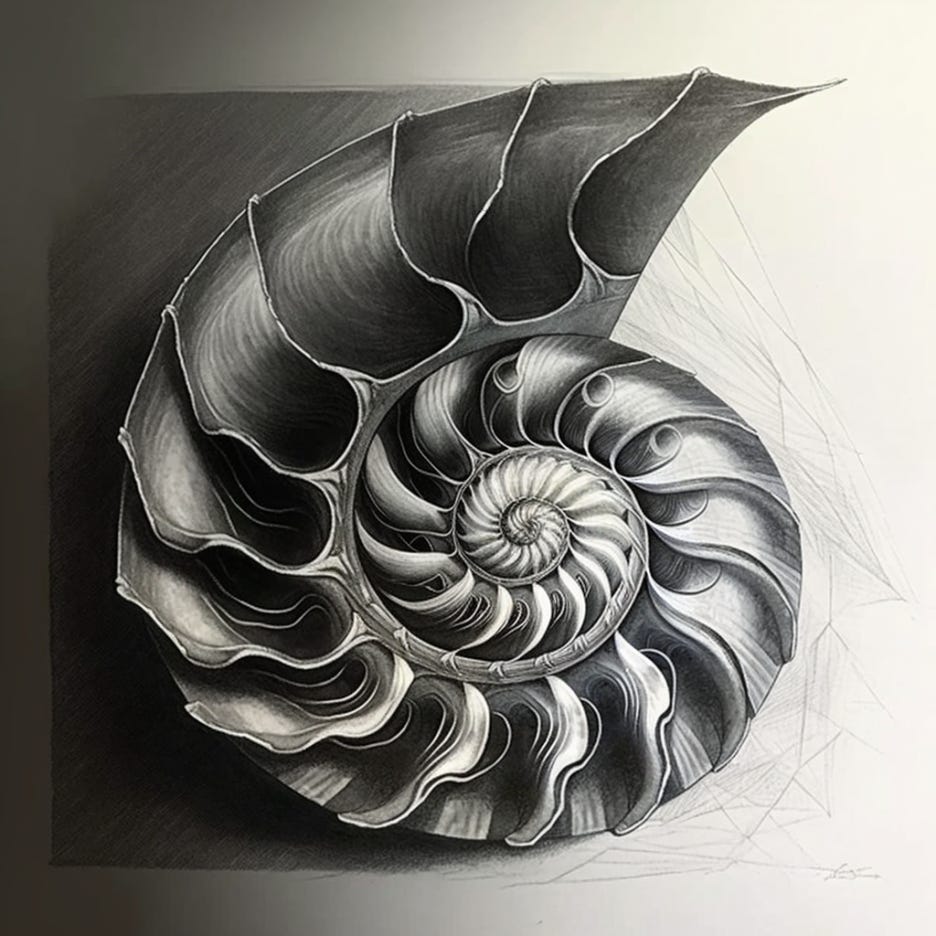

Eva, the botanical illustrator, sits next to me scratching away at her sketch pad. I find the sound soothing. It’s the rhythmic quality, I think. Whenever I look at what Eva is sketching, she repositions her shoulders like a schoolmate who thinks someone is trying to copy her work. This time, thanks to the distracting arrival of fresh coffee and breakfast cookies, I get a clean look and see she is drawing an amorphous shape that may or may not be a nautilus. Nothing she sketches has anything to do with the matter at hand. For reasons I can’t entirely explain, this makes me uneasy.

Via Midjourney3

A slight young man in his late twenties, Miguel, enters the interview room and sits at the table. Miguel has curly hair and hands he doesn’t seem to know what to do with. Unlike most, who playfully nod at the mirror and then sit down with a knowing smile, Miguel stares toward the observation area with grim foreboding. Also, Miguel initially declines to wear a headset.

“Oh, do you have an implant?” Anna asks.

Miguel shakes his head.

“Ok. Well. It’s no big deal. We just want to ask you a few questions about a product we’re working on and how you might use it,” Anna says.

“Fine,” says Miguel. The translation device adjusts to his voice, but I detect a subtle tell, a lack of breath that equates to a lack of rhythm. Eva’s charcoal makes music, but the translated voice drones with a metronomic lilt.

“Well, look,” Anna says. “It’s fine for us to talk in the usual way, but we’ve really here to test the interaction between the mind and the device, and our whole premise is that we want the communication to feel almost telepathic.”

Miguel accepts the nest of sensors and puts it on his head, a solemn man wearing a ridiculous crown. I make a note in my notebook: make the headset look less ridiculous.

Why does he look so forlorn? Is it something inherent in the interface? His affect is such that even the engineers look up from their displays, puzzled.

Anna slides the prototype of the device over Miguel’s wrist and we all wait.

The air conditioning continues to hiss. Eva’s charcoal scratches slow to a languid trickle and then stop completely.

“I want you to take four deep breaths,” says Anna.

X: I want the two-way mirror to disappear. I want the windows of the office building to disappear. I want for the line between the device and the viewers to evaporate completely so that it is as if we are as liquid as thought, inside the thoughts, able to actually understand them and empathize in a more direct and wordless way.

Y: Why?

X: That’s a good question.

Y: It feels as if you want to communicate something else entirely.

X: Maybe.

Y: What is it that you wish to communicate?

X: A feeling, but one that lacks precision. I thought maybe the two-way mirror or one-way mirror might describe it…how we might move from the two-way mirror to a window, or no window at all. But now I’m not so sure.

Y: Would you like to try and describe the feeling?

X: It’s a fear that I’ve underplayed my appreciation. Maybe I should just say what I mean. And what I mean is that I’ve noticed, after listening to subjects talk….you know whether they’re telling their best stories or sharing basic details, I feel more connected to the natural world. I feel tingly, if that makes any sense. I walk out into the world and I actually appreciate it.

Y: It sounds like nostalgia.

X: No it is reverence.

Y: I see. Would you like to continue?

No thanks. I need a walk. Let’s pick it up later. New form. New context.

This week’s recommendations:

Reading: How 1970s California Created the Modern World by Francis J Gavin via Engelberg Ideas

Listening: a softer focus by Claire Rousey and Casa by Morelenbaum² and Sakamoto. R.I.P Ryuichi. Ars longa, vita brevis. There is a beautiful video capturing some of the collaboration between this trio here.

Music credits for article audio:

Opening Theme: “Friendly Evil Gangsta Synth Hip Hop” by mesostic via Wikimedia Commons

Closing Theme: “Hopes” by Kevin MacLeod via Wikimedia Commons

Voices of X and Y created with ElevenLabs

GPT4

In his book Postmodern Geographies: The Reassertion of Space in Critical Social Theory (1989), Edward Soja describes the hotel as

a concentrated representation of the restructured spatiality of the late capitalist city: fragmented and fragmenting, homogeneous and homogenizing, divertingly packaged yet curiously incomprehensible, seemingly open in presenting itself to view but constantly pressing to enclose, to compartmentalize, to circumscribe, to incarcerate. Everything imaginable appears to be available in this micro-urb but real places are difficult to find, its spaces confuse an effective cognitive mapping, its pastiche of superficial reflections bewilder co-ordination and encourage submission instead. Entry by land is forbidding to those who carelessly walk but entrance is nevertheless encouraged at many different levels. Once inside, however, it becomes daunting to get out again without bureaucratic assistance. In so many ways, its architecture recapitulates and reflects the sprawling manufactured spaces of Los Angeles.[9]

PROMPT: a very rough hand-drawn sketch of an amorphous shape that may or may not be a nautilus charcoal on sketch paper black and white drawing is half-finished