Patch #33: Ghost prices

Dispatches from a journey into the physical world, by which I mean Walmart

1.

In mid-January of 2025, a rush of arctic air blew into the mountain west, dropping the windchill far below zero and driving social media sorts to go outside and throw boiling water into the air so we could watch it turn to ice. I had a beeping smoke alarm and had run fresh out of batteries. Facing a sleepless night, I decided to drive to Walmart. I know this has the makings of a real corker of a yarn, but please stay with me.

Why would I leave the house on such a Siberian night and head for the Walmart? I’ve observed the prices at the cavernous discounter are often markedly cheaper than they are on Amazon, and absolutely lower than they are at Walgreens, King Soopers, Safeway, or of course 7-Eleven, all of which are much closer to my Denver home than the Walmart store on Quebec. Enduring some inconvenience to save money makes me feel virtuous. I’m suspicious of the insane ease of ordering batteries through a voice assistant and the cent-siphoning tendencies of the popular applications of our day. As a longtime remote worker, I sometimes pine for excuses to encounter the physical world. I should also note that, my wife Michelle being in India, I was heading into week 3 of solo parenting. The idea of a 20-minute car ride spent in luxurious silence had a lot of allure, weather be damned.

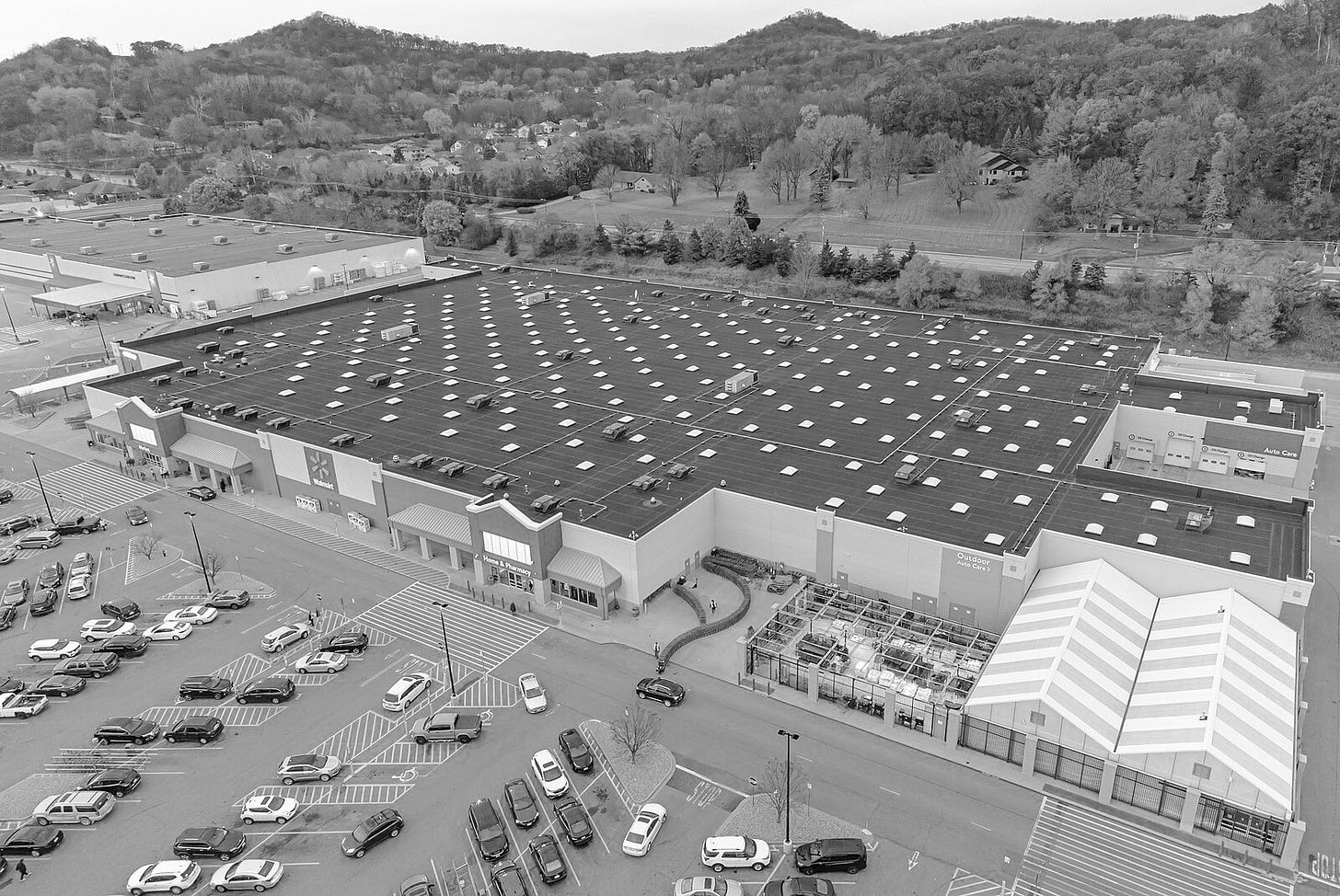

The Walmart in Central Park on Quebec is an artifact of the big box retail era, not too far from a Home Depot, a Sam’s Club, and a semi-terrifying Cajun seafood restaurant called the Hook & Reel that strives to bring the humid charms of the bayou here to the High Rockies. I’m sure you know exactly what this kind of retail environment looks like. The parking lots are vast, the boulevards en route to the destination are expansive, and all of the buildings in the development are in possession of a scale and shape reminiscent of nothing so much as an Amazon warehouse or hastily assembled third-party prison spotted from a desolate stretch of freeway. Long-discouraged European urban planners might note this isn’t even a fifteen-minute parking lot, let alone a fifteen-minute city.

I thought that on an evening like this parking would be plentiful given the much-discussed arrival of arctic air local weathermen reported on in a tone more appropriate for describing the arrival of an alien species, but it turns out I was wrong. A lot of people were at the Walmart, and they were stocking up. I found a spot in the farthest reaches of the lot because, like my father before me, I now live in fear of door dings, and try to park in a spot with spaces on both sides—guaranteeing a mall crawler with neon lighting accents will pull into the space next to me and deliver the very fate I sought to avoid.

I noticed some things on my way into the store. A lot of people sat in their cars watching screens while waiting for others to shop for them (I think). The engines ran to keep the vehicles warm, and the curling exhaust fumes surrounding the glowing, phone-lit interiors looked like stage smoke in the lights of the parking lot. The shopping hauls being loaded into these waiting cars were large, and some included survivalish supplies like 2 gallon water jugs and bulk foods. Was it because of the cold? There was a conspicuous police presence in the confines of the store. I counted four cruisers, parked adjacent to the entrance like the trophy cars selected by the valet staff to signal exclusivity, except these vehicles were meant to scare organized rings of thieves who have been plaguing stores like Walmart, Target, and others with large-scale organized retail theft. As if shoppers didn’t get the point from the cars outside, there was a sign on the entrance gate to the store proudly announcing the partnership of Walmart with the Denver police department to keep everyone safe.

I do like Walmart. Mostly, it’s because of the aforementioned prices, but also because I have nostalgic memories of visiting the stores in the past. I remember my grandfather looking at fishing lures for what felt like hours, or walking through the toy section with a fist full of Christmas dollars. When I was younger and would come across those judgy “people of Walmart” photos making fun of the sartorial choices and fitness of Walmart shoppers, I bristled at the snobby cruelty of the whole exercise. Walmart doesn’t pretend to be anything other than it is. Growing up, my father would pay me good American money to read the Forbes 400 and report on what I’d learned about the people who populated the list. His hopes were to stir my capitalist animal spirits—an effort I rewarded by getting an MFA in fiction. I do remember the stories in these Forbes issues of fortunes made against great odds: Bill Gates dropping out of Harvard, Ralph Lauren (nee Lifshitz) selling ties, and of course Sam Walton, still alive then, enduring bankruptcy before striking gold with the Walmart concept.

Of all the billionaires on the list, Walton was perhaps my favorite. Even after making his fortune, he would drive his F150 from store to store, sometimes with his dogs, anonymously surveying his retail kingdom in a lo-fi-no-bullshit way that reinforced its success. Employees developed the belief that if they touched the door handle of Walton’s truck they would be blessed for life with the gift of frugality.

It’s true that Walmart has decimated small businesses and robbed many a main street of its utilitarian charm, forcing us all to endure the great micro-brewery explosion of the aughts, barre studios, paint-by-numbers franchises, and the like. But the unfortunate truth is that most prefer cheap goods to charm, especially for uncharming goods, and as of the time of writing this does remain a market economy. To make up for its assault on small businesses, Walmart let people park their RVs in the parking lot. They hired affable senior citizens to put on the blue vest and greet shoppers. I do not have the undying loyalty to Walmart that I have to, say, Costco, but I like the place just fine. The store does have its eccentricities, but if you can’t countenance a towering figure in a batman cape who is doing no harm to you other than warning the second coming is imminent, you can stay home and buy your Chinese goods on Amazon. I’m pretty sure that unlikely prophet has more authority to invoke the voice of God than those who profit off its mention.

There were no greeters when I made my way into the Walmart to hail me with a hearty “Good evening” or “Howyoudoin?” and tell me where the batteries were. In fact, there was very little help at all. I wandered first to the home goods section, where I drifted through aisles of LED bulbs and microwaves and rice cookers, but batteries were nowhere to be found. I did find other things: a dizzying array of homey candles throwing off an exaggerated potpourri miasma, automotive supplies, sporting goods, and lawn & garden implements, treatments, and adornments. Goods, goods everywhere, and not a battery to buy. Because no one was around to offer help, I pulled up ChatGPT on my phone and asked where batteries were usually located in a typical Walmart. ChatGPT, with characteristic confidence, told me that they were located in the electronics section “next to the charging cables and phone accessories,” which made sense to me.

The electronics section possessed headphones and records, both passions of mine (I never touched the door handle of Walton’s truck), so I perused the goods and noted that LPs at Walmart aren’t that much cheaper than they are anywhere else. Because the headphones at Walmart cater to sensible consumers and are not manufactured by obscure midwestern artisans or salaried Japanese craftsmen in lab coats, they were of little interest. There were other items of interest in the section that did grab my attention, including a pretty good swath of video games, but AA batteries were nowhere to be found.

Many of the goods in the electronics section, mirroring a trend elsewhere in the store, were secured behind wires and locked plexiglass shields to prevent theft, an unfortunate arrangement that makes it hard to buy things when you can’t find someone to unlock the apparatus. At least Walmart has goods on the shelf. My local Walgreens on Colfax has the same locks, but the shelves are almost empty save for a few stray products soldiering on through the drugstore apocalypse. The store looks somewhat unhinged, with empty shelves that call to mind the looting after a natural disaster juxtaposed against cheery corporate messaging and imagery. The employees seem to avoid eye contact, perhaps because they don’t want to explain how an organization with a $10 billion market cap no longer stocks pens, notebooks, or deodorant. Recently, the Walgreens CEO sheepishly admitted that locking everything up creates a “hassle cost” that hurts sales.

Reflecting on my difficulties, it occurred to me that I have often found batteries in grocery stores, and that this Walmart had a whole grocery store of its own on the other side of the store, which was only a ten minute walk away. The aisles in the grocery section were well provisioned and busy, evoking a store within a store where commerce carries on as usual. I was briefly distracted by the sheer volume of the sauces available to consumers and remembered spending too much time reading an article asserting that a “condiment invasion” is dividing households.

I headed back to home goods, thinking I must have missed something. Seeing that I had not, I finally relented and asked a competent-looking stockist for assistance. She beamed at the opportunity. “Ah,” she said, “If you want to find batteries, you need to go to the jewelry section. Look for the large display that says ‘batteries’ in big letters.” She was so warm and confident that I thought maybe I’d been too hasty with my prognostications of Walmart’s decline.

I walked to the jewelry section and found it stocked with a selection of cheap Chinese watches and a few pretty nice Timex’s that briefly drew my interest until I remembered my quest. Reader, there were no batteries of any sort.

This failed endeavor into the frozen night had officially arrived at a recursive, dreamlike absurdity. As I plotted my next strategy, I encountered a lonely robot mopping the floors, leaving a wet streak in its wake. The hulking bruiser barreled ahead with a slight cant, like a drunk nepobaby trying to walk a straight line for a state trooper on a desolate two-lane road in Wyoming. Instead of an orderly line of moistened cleanliness, the robot veered toward an aisle of barricaded drugstore goods, then corrected itself, went into reverse, and repeated its unfortunate path. The crooked moplines on the floor contrasted with the dirt left by winter boots like tire tracks in the snow.

I finally relented and went to the customer service section for help. I did not have to ask for help because there, adjacent to the help desk, was a bursting endcap of all the batteries you could ever want. I bought AAAs, AAs, and some D’s for good measure. I checked my phone for a quick price comparison. Indeed, the batteries were cheaper than they were on Amazon, and I stocked up because I didn’t want to repeat this experience any time soon. There were maybe 30 self-checkout kiosks at the front of the store. All of them were broken. So I waited in line behind bulk grocery buyers for a human to check me out.

2.

Driving home, the designer in me contemplated the state of affairs. Years ago, it became a cliche to talk about a harmonious blend of the digital and the physical. I remember that some brave souls—likely the same folks who said “glocal”—even used the cringy portmanteau “phygital” to describe this purportedly emerging ideal. During COVID, there was much excitement about buy online, pick up in store as an exemplar of such a world and what McKinsey, with the subtlety of sixties radicals penning their first manifesto, breathlessly coined “the quickening” of digital transformation. In meetings with our clients and customers, those of us in technology and design-related fields shared storyboards articulating a seamless transition between digital convenience and real-world interaction, a symbiotic dance that would improve both realms.

To be fair, there are instances where the dream is realized. If I’m playing music in my kitchen and I step into my car, the same song automatically fills the vehicle when I close the door. I can track my pizza. I can find my luggage, my airpods, and my keys. I can pull up the Doordash app and order anything my heart desires, even if it makes me feel guilty as hell to do it. Some day soon drones will drop things in my backyard thirty minutes after I press the button or give verbal okay to my AI agent.

It is inarguable that digital experiences, and the convenience they deliver, have made some aspects of our lives better over the last fifteen years. But less often examined is the commensurate degradation of some physical experiences, which require a more sophisticated understanding of human behavior to design well that goes beyond optimizing for speed.

Perhaps no example better illustrates this dynamic than Starbucks. The multinational coffee chain invested heavily in digital convenience over the last decade. As a result, baristas are often overwhelmed by online orders with an endless variety of customizations and the expectation that everything will be ready when customers who ordered using the app step into the cafe. The people who are actually in the cafe, or stopped by spontaneously, endure a degraded experience: baristas who no longer have the time to exchange small talk, longer waits, lower quality drinks, and the energetic intrusion of rushed online orderers (I am sometimes one) who crowd the pick-up areas waiting impatiently for their caffeinated sugarbombs. Some have pointed to this dynamic, among others, as one of the reasons Starbucks’s financial performance has declined. In response, the company has promised to invest more in technology and “bring back a more personal coffeehouse atmosphere with comfortable seating and the cafe experience for which Starbucks was originally known.”

I have doubts they will achieve this without a radically different approach that balances technology investment with thoughtful human observation. Instead of focusing so ardently on “blending” the digital and physical as products like Meta’s glasses promise to do, it might be better design practice to strive for a more sophisticated cleaving of realms that newer technologies enable. Increasingly, I’ve been thinking about an updated delineation between front-of-house and back-of-house. Imagine a Starbucks where robots prepare drink orders in a back room and send them to a drive-thru pick-up, but in the cafe, it’s 1995. The baristas are attentive to every walk-in customer. Customers are free to linger, talk, and work in peace. The drinks are hand-made and customized according to spontaneous customer whims. The invisible technology enhances the physical experience rather than degrades it.

We get a sharper view on such ideas when we realize how many automation efforts put the onus on the consumer to do more work. Self-checkout kiosks often force us to solve problems we’d rather not solve, like looking up PLU numbers or determining the weight of our oranges. In a rapidly arriving future where we can offload this work to AI agents that don’t force us to spend so much time looking at screens and picking our way through menus, we have to rethink how the puzzle pieces fit together when designing an experience.

There will still be a lot of modes when we want things instantly. We’ll ask our agents to order batteries; we’ll want our coffee drinks in four minutes or less; we’ll scan the skies impatiently waiting for the drone to deliver laundry detergent so we can wash the soccer jersey in time for the game.

But I don’t think these possibilities will diminish the desire for better experiences in the world, and they won’t push us to want real-world experiences that mimic the optimization of an impersonal digital experience. Discourse often focuses on the numbing isolation of our feeds and our distractions, but it fails to acknowledge the growing craving these behaviors signal for real world experiences that feel more real. My Starbucks example is admittedly a little trivial, but imagine similar dynamics at a school, a social gathering, or in an office and you get a sense of the possibility space and its allure. I have a hunch there is an underlying motivation driving a desire for heightened awareness. We live in a world where you can take an idea and write a pretty credible research paper in an hour using OpenAI’s Deep Research tool. But where do you get your idea from in the first place? As Tobias Rees notes in a recent Noema interview

No matter how smart AI is, it cannot be smart for me. It can provide me with information, it can even engage me in a thought process, but I still need to orient myself in terms of my thinking. I still need to have my own experiences and my own insights, insights that enable me to live my life.

We need our perceptions and experiences more than ever to take advantage of the novel affordances these tools represent, and we need physical environments that accept this reality rather than rushing headlong to add more layers of abstraction.

I get the sense I’m missing something. I question my desire to make too much of a trip to Walmart. Reading over my observations, I see things between the lines that worry me. Are the customers stocking up because of the cold, or are they buying in bulk to hunker down and hide from those who might deport them? Are the glowing screens in the car playing mind-numbing Tiktok pranks, or are people checking on loved ones? Is the store itself a little shabby because it’s passing its savings on to its customers, or is it a microcosm of a glitchy surveillance state where robots drift off-program under a bank of blinking fluorescent lights? I don’t know the answers to any of these questions, but maybe that’s the point. If you stay home, you don’t ask them. If you don’t write them down, you don’t interrogate them. If you don’t interrogate them, you don’t think. And if you don’t think…well…that knock at the door might be announcing something other than the arrival of a package.

Recommendations:

Reading: Meditations for Mortals, by Oliver Burkeman

Listening: Piedras 2, by Nicolas Jaar

Music credits for article audio:

Opening Theme: “Cepheid Disk” by Airglow via Wikimedia Commons

Closing Theme: “Comfort in Uncertainty” by bbatv via Wikimedia Commons

What a great piece! I think about this a lot. In France, many spaces and practices have stayed the same for so long that it's become part of what drives people to visit here while simultaneously prompting frustration (Lines are so long! Why does the baker have to talk to every person and wrap each purchase separately? Why won't the waiter deliver the bill? Can't they see I've finished eating?)... what people miss/forget/ignore are the preciously held (and very human-based) norms and manners that conflict with productivity and efficiency above all else. BUT, the answer moving forward can't just be to look back with fondness and nostalgia. I'll be very curious to see where it all leads. Thank you for writing and look forward to reading more. -Romy

Love this comment. Fascinating to think about a way forward in different cultural contexts with different norms and manners. Thanks for sharing, Romy.